The Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes

The Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes

edited by John S. Dinger

foreword by Morris A. Thurston

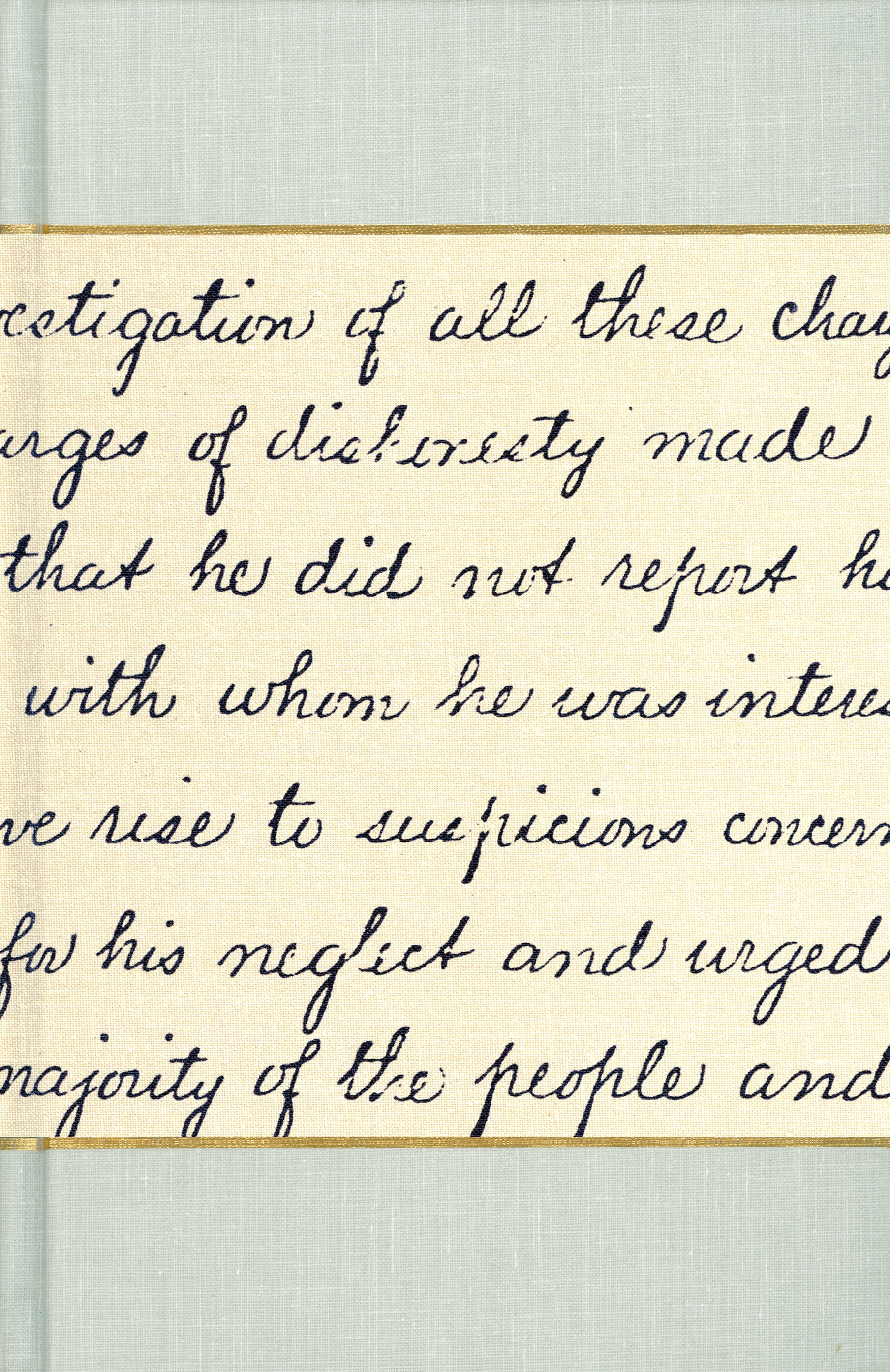

Two incidents are particularly dramatic in this volume, thanks to the careful work of clerks who took the minutes, bringing to life some key moments in LDS history. One of the most memorable meetings of the city council occurred on June 10, 1844; the minutes capture the emotions as members debate whether to destroy the opposition newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor. The publisher of the paper, Sylvester Emmons, had been a councilman until his June 8 expulsion for having “lifted his hand against the municipality of God Almighty.” As the hawkish councilmen became increasingly agitated, they began shouting slogans, asking whether the others had the nerve to do what was right and crush the newspaper. The answer was a sustained, raucous cheer.

“Yes resounded from every quarter of the room,” the clerk, Willard Richards, wrote. “Are we offering . . . to take away the right[s] of anyone [by] this [action][to]day?” one of the city councilmen, William Phelps, shouted. “No!!!” was the answer “from every quarter.” Should they also tear down the barn of newspaper editor Robert Foster? Yes! they said. By the time the meeting was over, the Nauvoo police, assisted by one hundred soldiers of the Nauvoo Legion, had “tumbled the press and materials into the street and set fire to them, and demolished the machinery with a sledge-hammer.”

Another gripping event occurred on September 8, 1844, when the high council gathered outdoors to accommodate large crowds for the trial of Sidney Rigdon of the First Presidency. A behind-the-scenes power struggle became evident as Brigham Young stepped forward to take control of the meeting, culminating in a request for a vote from the audience. Young asked everyone to “place themselves so that [he] could see them, so he would “know who goes for Sidney.” There followed a flurry of denunciations of various church members who were summarily excommunicated by acclimation rather than by trial in a meeting lasting six hours.

Perhaps it all made sense if you were there and knew what the rules were, but for most people today, the history of Nauvoo seems like a parade of horribles. For instance, Henry Cook was brought before the high council on the charge of having sold his wife for her weight in catfish. He and the buyer were happy, but she was not. Henry was found innocent “under the circumstances” because “the cat fish woman” was found to be a shrew.

In another case, Joseph Smith charged William Sagers with “using my name in a blasphemous manner,” saying Smith had given him permission to sleep with his wife’s sister. William apologized, and within a month Joseph actually did give William official permission to marry his sister-in-law. This enraged his wife, Lucinda, who complained to the high council. In rejecting her complaint, the council said it had already acquitted Sagers and would not take up the case again. The minutes reveal that the trial was held in a room that was “crowded to excess’ with curious onlookers, which is vastly different than the strict privacy observed in LDS trials today.

In September 1845, the council considered the case of Amasa Bonney, who was charged with public drunkenness—an especially serious offense for a Latter-day Saint. But unfazed, Bonney “appeared [before the council] in a high state of intoxication, with a bottle in his pocket; and was soon in a state of sleep in the council room, whereupon it was voted unanimously that he be cut off from the Church.” Some people fared better and were both excommunicated and reinstated all in the same meeting because they quickly confessed and repented.

On the other side of a thin wall separating church and state in Nauvoo, the annals of the city council (as opposed to the high council) are just as curious. The council passed a law forbidding the sale of whiskey “in less quantity than a gallon.” In other words, whiskey could only be sold in large quantities. An exception was made for Joseph Smith, who pointed out that because his large home served as a hotel for visitors, he had been forced to build a bar in the foyer. He was therefore given permission to sell whiskey by the drink. From subsequent discussions, it seems to have been a profitable endeavor.

The city council dealt with all sorts of problems, large and small. In 1841 it threatened to kill free-roaming dogs and pigs, but two years later it had a change of heart. Now it specified that “cows, calves, sheep, goats, and harmless and inoffensive dogs shall be suffered to run at large as free commoners” without fear of harm. The reason for this was that Joseph Smith had decided “God withdrew his spirit from the earth . . . because the people were so ready to take the life of animals.”

The only thing more dramatic than the city’s response to everyday matters was its failings in local and national diplomacy. In 1843, when it had grown tired of negotiating with public officials from neighboring counties, the city council petitioned the US Congress to see if Nauvoo could break away from the State of Illinois and become a free, independent city, also to ask if Joseph Smith might be given authority over US troops. Despite a polite no from Washington, the city advised its lobbyists to be persistent, the mayor, Joseph Smith, advising them on how to persuade Senators by offering them drinks and entertainment.

All of which is to say that there are plenty of surprises in this volume for even a seasoned Mormon history buff—everything brought into sharp focus through the expertise of the editor, John S. Dinger. As one example of how the material has been placed into context for the reader, the city council complained that after the Nauvoo Expositor was destroyed, a “mob” gathered and was threatening the city. The police made a list of the mobocrats. As Dinger learned by looking up the named individuals, they were not terrorists but were the fifteen-to-seventeen-year-old sons of good Mormon families who had gathered to watch the spectacle of the police destroying the printing press.

hardback: $29.00 | ebook: $9.99

The Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes

edited by John S. Dinger

foreword by Morris A. Thurston

Two incidents are particularly dramatic in this volume, thanks to the careful work of clerks who took the minutes, bringing to life some key moments in LDS history. One of the most memorable meetings of the city council occurred on June 10, 1844; the minutes capture the emotions as members debate whether to destroy the opposition newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor. The publisher of the paper, Sylvester Emmons, had been a councilman until his June 8 expulsion for having “lifted his hand against the municipality of God Almighty.” As the hawkish councilmen became increasingly agitated, they began shouting slogans, asking whether the others had the nerve to do what was right and crush the newspaper. The answer was a sustained, raucous cheer.

“Yes resounded from every quarter of the room,” the clerk, Willard Richards, wrote. “Are we offering . . . to take away the right[s] of anyone [by] this [action][to]day?” one of the city councilmen, William Phelps, shouted. “No!!!” was the answer “from every quarter.” Should they also tear down the barn of newspaper editor Robert Foster? Yes! they said. By the time the meeting was over, the Nauvoo police, assisted by one hundred soldiers of the Nauvoo Legion, had “tumbled the press and materials into the street and set fire to them, and demolished the machinery with a sledge-hammer.”

Another gripping event occurred on September 8, 1844, when the high council gathered outdoors to accommodate large crowds for the trial of Sidney Rigdon of the First Presidency. A behind-the-scenes power struggle became evident as Brigham Young stepped forward to take control of the meeting, culminating in a request for a vote from the audience. Young asked everyone to “place themselves so that [he] could see them, so he would “know who goes for Sidney.” There followed a flurry of denunciations of various church members who were summarily excommunicated by acclimation rather than by trial in a meeting lasting six hours.

Perhaps it all made sense if you were there and knew what the rules were, but for most people today, the history of Nauvoo seems like a parade of horribles. For instance, Henry Cook was brought before the high council on the charge of having sold his wife for her weight in catfish. He and the buyer were happy, but she was not. Henry was found innocent “under the circumstances” because “the cat fish woman” was found to be a shrew.

In another case, Joseph Smith charged William Sagers with “using my name in a blasphemous manner,” saying Smith had given him permission to sleep with his wife’s sister. William apologized, and within a month Joseph actually did give William official permission to marry his sister-in-law. This enraged his wife, Lucinda, who complained to the high council. In rejecting her complaint, the council said it had already acquitted Sagers and would not take up the case again. The minutes reveal that the trial was held in a room that was “crowded to excess’ with curious onlookers, which is vastly different than the strict privacy observed in LDS trials today.

In September 1845, the council considered the case of Amasa Bonney, who was charged with public drunkenness—an especially serious offense for a Latter-day Saint. But unfazed, Bonney “appeared [before the council] in a high state of intoxication, with a bottle in his pocket; and was soon in a state of sleep in the council room, whereupon it was voted unanimously that he be cut off from the Church.” Some people fared better and were both excommunicated and reinstated all in the same meeting because they quickly confessed and repented.

On the other side of a thin wall separating church and state in Nauvoo, the annals of the city council (as opposed to the high council) are just as curious. The council passed a law forbidding the sale of whiskey “in less quantity than a gallon.” In other words, whiskey could only be sold in large quantities. An exception was made for Joseph Smith, who pointed out that because his large home served as a hotel for visitors, he had been forced to build a bar in the foyer. He was therefore given permission to sell whiskey by the drink. From subsequent discussions, it seems to have been a profitable endeavor.

The city council dealt with all sorts of problems, large and small. In 1841 it threatened to kill free-roaming dogs and pigs, but two years later it had a change of heart. Now it specified that “cows, calves, sheep, goats, and harmless and inoffensive dogs shall be suffered to run at large as free commoners” without fear of harm. The reason for this was that Joseph Smith had decided “God withdrew his spirit from the earth . . . because the people were so ready to take the life of animals.”

The only thing more dramatic than the city’s response to everyday matters was its failings in local and national diplomacy. In 1843, when it had grown tired of negotiating with public officials from neighboring counties, the city council petitioned the US Congress to see if Nauvoo could break away from the State of Illinois and become a free, independent city, also to ask if Joseph Smith might be given authority over US troops. Despite a polite no from Washington, the city advised its lobbyists to be persistent, the mayor, Joseph Smith, advising them on how to persuade Senators by offering them drinks and entertainment.

All of which is to say that there are plenty of surprises in this volume for even a seasoned Mormon history buff—everything brought into sharp focus through the expertise of the editor, John S. Dinger. As one example of how the material has been placed into context for the reader, the city council complained that after the Nauvoo Expositor was destroyed, a “mob” gathered and was threatening the city. The police made a list of the mobocrats. As Dinger learned by looking up the named individuals, they were not terrorists but were the fifteen-to-seventeen-year-old sons of good Mormon families who had gathered to watch the spectacle of the police destroying the printing press.

hardback: $29.00 | ebook: $9.99

The Nauvoo City and High Council Minutes

edited by John S. Dinger

foreword by Morris A. Thurston

Two incidents are particularly dramatic in this volume, thanks to the careful work of clerks who took the minutes, bringing to life some key moments in LDS history. One of the most memorable meetings of the city council occurred on June 10, 1844; the minutes capture the emotions as members debate whether to destroy the opposition newspaper, the Nauvoo Expositor. The publisher of the paper, Sylvester Emmons, had been a councilman until his June 8 expulsion for having “lifted his hand against the municipality of God Almighty.” As the hawkish councilmen became increasingly agitated, they began shouting slogans, asking whether the others had the nerve to do what was right and crush the newspaper. The answer was a sustained, raucous cheer.

“Yes resounded from every quarter of the room,” the clerk, Willard Richards, wrote. “Are we offering . . . to take away the right[s] of anyone [by] this [action][to]day?” one of the city councilmen, William Phelps, shouted. “No!!!” was the answer “from every quarter.” Should they also tear down the barn of newspaper editor Robert Foster? Yes! they said. By the time the meeting was over, the Nauvoo police, assisted by one hundred soldiers of the Nauvoo Legion, had “tumbled the press and materials into the street and set fire to them, and demolished the machinery with a sledge-hammer.”

Another gripping event occurred on September 8, 1844, when the high council gathered outdoors to accommodate large crowds for the trial of Sidney Rigdon of the First Presidency. A behind-the-scenes power struggle became evident as Brigham Young stepped forward to take control of the meeting, culminating in a request for a vote from the audience. Young asked everyone to “place themselves so that [he] could see them, so he would “know who goes for Sidney.” There followed a flurry of denunciations of various church members who were summarily excommunicated by acclimation rather than by trial in a meeting lasting six hours.

Perhaps it all made sense if you were there and knew what the rules were, but for most people today, the history of Nauvoo seems like a parade of horribles. For instance, Henry Cook was brought before the high council on the charge of having sold his wife for her weight in catfish. He and the buyer were happy, but she was not. Henry was found innocent “under the circumstances” because “the cat fish woman” was found to be a shrew.

In another case, Joseph Smith charged William Sagers with “using my name in a blasphemous manner,” saying Smith had given him permission to sleep with his wife’s sister. William apologized, and within a month Joseph actually did give William official permission to marry his sister-in-law. This enraged his wife, Lucinda, who complained to the high council. In rejecting her complaint, the council said it had already acquitted Sagers and would not take up the case again. The minutes reveal that the trial was held in a room that was “crowded to excess’ with curious onlookers, which is vastly different than the strict privacy observed in LDS trials today.

In September 1845, the council considered the case of Amasa Bonney, who was charged with public drunkenness—an especially serious offense for a Latter-day Saint. But unfazed, Bonney “appeared [before the council] in a high state of intoxication, with a bottle in his pocket; and was soon in a state of sleep in the council room, whereupon it was voted unanimously that he be cut off from the Church.” Some people fared better and were both excommunicated and reinstated all in the same meeting because they quickly confessed and repented.

On the other side of a thin wall separating church and state in Nauvoo, the annals of the city council (as opposed to the high council) are just as curious. The council passed a law forbidding the sale of whiskey “in less quantity than a gallon.” In other words, whiskey could only be sold in large quantities. An exception was made for Joseph Smith, who pointed out that because his large home served as a hotel for visitors, he had been forced to build a bar in the foyer. He was therefore given permission to sell whiskey by the drink. From subsequent discussions, it seems to have been a profitable endeavor.

The city council dealt with all sorts of problems, large and small. In 1841 it threatened to kill free-roaming dogs and pigs, but two years later it had a change of heart. Now it specified that “cows, calves, sheep, goats, and harmless and inoffensive dogs shall be suffered to run at large as free commoners” without fear of harm. The reason for this was that Joseph Smith had decided “God withdrew his spirit from the earth . . . because the people were so ready to take the life of animals.”

The only thing more dramatic than the city’s response to everyday matters was its failings in local and national diplomacy. In 1843, when it had grown tired of negotiating with public officials from neighboring counties, the city council petitioned the US Congress to see if Nauvoo could break away from the State of Illinois and become a free, independent city, also to ask if Joseph Smith might be given authority over US troops. Despite a polite no from Washington, the city advised its lobbyists to be persistent, the mayor, Joseph Smith, advising them on how to persuade Senators by offering them drinks and entertainment.

All of which is to say that there are plenty of surprises in this volume for even a seasoned Mormon history buff—everything brought into sharp focus through the expertise of the editor, John S. Dinger. As one example of how the material has been placed into context for the reader, the city council complained that after the Nauvoo Expositor was destroyed, a “mob” gathered and was threatening the city. The police made a list of the mobocrats. As Dinger learned by looking up the named individuals, they were not terrorists but were the fifteen-to-seventeen-year-old sons of good Mormon families who had gathered to watch the spectacle of the police destroying the printing press.

hardback: $29.00 | ebook: $9.99

John S. Dinger is a graduate of the S. J. Quinney College of Law, University of Utah, where he was an editor at the Utah Law Review. He is presently Deputy Prosecuting Attorney for Ada County in Boise, Idaho. He has published in the Idaho Law Review, Journal of Mormon History, and Utah Law Review. He is also the editor of the volume, Significant Textual Changes in the Book of Mormon: The First Printed Edition compared to the Manuscripts and the Subsequent Major LDS English Printed Editions and is a member of the editorial board of the Mormon History Association. He and his wife have three children.

Documentary History, History

ISBN: 978-1-56085-214-8